The following paper was written for the Archaeology of Media (MIAS 220) course, taught by Michael Friend, Technical Specialist at Sony Pictures. The course focused on the technological history of moving images, and this was my final paper for the class. My awareness of the negligible amount of attention and publicity given to videotape preservation (in comparison to film) informed my decision to write this paper.

Although much progress has been made in the crisis of film preservation, the crisis of videotape preservation remains as large as ever. Videotape preservation does not have the same romanticism and appeal to the masses as the preservation and restoration of a feature film, but videotape contains footage that is just as culturally significant and important to preserve.

The crisis in videotape preservation arises from the fact that the medium was never designed to be a preservation medium, nor to last a significant amount of time. Of the major threats to preserving videotape, two in particular stand out. One is what was originally seen as the advantage of videotape over film – it can be recorded over and reused. The other is the rapid obsolescence of the generations of formats that have come and gone since the introduction of magnetic videotape in the mid 1950’s as a method for recording television.

Thousands of hours of broadcast recordings of historical events in the 1960s and 1970s have vanished due to the poor or non-existent preservation standards of television networks and the medium’s inherent lack of durability.

According to Jim Lindner, what is at risk is virtually the entire inventory of recorded media “from master audio recordings of symphonies to videotape recordings of the news gathered over the last 40 years. Virtually our entire audio and visual heritage from the 1940’s to the 1980’s is in serious jeopardy.”

Like radio, television began as a live format and was seen to some degree as radio’s visual counterpart. The novelty of television was due to the fact that, unlike cinema, it was live. In the infancy of the television age, there was no perceived need to record material or broadcasts. However, as television increased in popularity, broadcasters realized the need to record material for subsequent broadcasts in different time zones, and because the networks’ legal departments needed a record of broadcasts in case of legal action against them.

Television material and broadcasts were originally recorded on film, using either telecine devices or kinescopes. This was not an optimal method for recording television due to the difference in frame rates between film and television, and also due to the inferior recording quality of the kinescopes when compared to the broadcasts themselves. For the first twenty years of television, no method of electronically recording broadcasts existed because the volume of bandwidth (analog signal information) consumed by a broadcast signal was greater than with audio.

The seizing of magnetic tape technology from the Nazi’s in the aftermath of World War II spurred the research in audio and video recording in the United States. The first working prototype of video recording owed its existence to Bing Crosby, who in the late 1940s was one of the first radio performers to pre-record his broadcasts on tape. Crosby did this to reduce his workload and prevent the need for live performances in different time zones. In 1948 Crosby was recording regularly on television, and he solicited the engineer and Army Signal Corps. Officer John J. Mullin to produce a magnetic tape recorder for video signals. Mullin obliged and the result was the Mullin-Crosby videotape recorder, which recorded black-and-white picture on 1/2” magnetic tape.

Since television is an encoded signal, it must to be recorded in an encoded form. The video tape recorder (VTR) was the first commercially practical device that was able to do this. Shortly after the introduction of the Crosby-Mullin VTR, the British Broadcast Corporation (BBC) demonstrated its Visual Electronic Recording Apparatus (VERA) in 1953. The technology in this machine was the first step in enabling videotape to become a standard production technology in television studios and be adapted for commercial use. However, both the VERA and Crosby-Mullin VTRs had one major issue that would keep them from obtaining the popularity that the future 2-inch Quadruplex would obtain – their high tape speeds (200 inches per second for the VERA and 240 for Crosby-Mullin). These high tape speeds severely limited the running time available on each reel and resulted in high levels of mechanical wear to the machines.

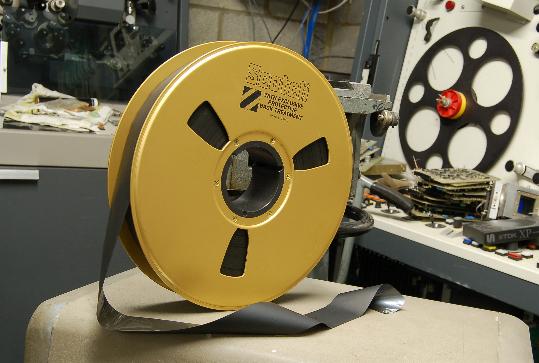

The American Ampex Corporation was founded in 1944 specifically to profit from magnetic audiotape technology. By the 1950s it was working on ways to reduce tape speed and increase the image quality that could be obtained from linear VTRs. Ampex’s research and labor resulted in the VRX-1000, introduced in March 1956. The VRX-1000 was a VTR that used 4 rotating heads mounted in a cylindrical assembly, across which 2 inch magnetic tape would pass at a speed of 30 inches per second. This was a drastic reduction in tape speed from both the VERA and Crosby-Mullin. The 4 rotating heads assembly inspired the name for the 2-inch Quadruplex (or 2-inch Quad).

The quality of the recordings made on 2-inch Quads surpassed those that had been made on film via kinescopes and they were practically indistinguishable from live broadcast when viewed at home. Despite the high quality of the 2-inch Quad recordings, there were several drawbacks that discouraged it from being a primary production medium. For example, a tape’s recording could only be played back on the machine that recorded it. In addition, there were difficulties and constraints in editing as well as mechanical wear on the heads after just a few hundred hours of operation. These drawbacks would also lead to later problems in preservation.

The 2-inch Quadruplex videotape was developed in 1956 by the American Ampex Corporation. One of the advantages it held over film, was its ability to be recorded over and reused multiple times. Unfortunately, this advantage led to the loss of vast amounts of culturally significant material.

Nonetheless, videotape had several advantages over film: it was cheaper; recordings could be played back instantly, thereby eliminating the need for processing, and tapes could be recorded over and reused multiple times. Unfortunately, it was this last advantage that led to the loss of culturally significant and historical material due it being “missing, believed wiped”.

Almost all broadcast television was recorded on Ampex’s 2-inch Quad, from its introduction in the mid-1950s until its replacement in the 1970s. Few of the tens of thousands of recordings that were made still exist, and there are numerous reasons for such a drastic loss of an enormous amount of footage. When VTRs were originally being used to record television programming, no one realized the content that was being recorded would be an economic and cultural asset in the future. Nor did they realize that this asset would be worth more than the cost of the media it was being recorded on. The machines themselves were expensive, costing upwards of $75,000 when they first came on the market. Ampex justified this high price by telling buyers that the tapes could be erased and re-recorded very easily. Once a tape was re-recorded, its previous material was lost forever. “Indeed, when one’s business is to produce 24 hours of programming a day, the huge task at hand is to create a vast quantity to the new material; what happened yesterday or even ten minutes ago is no longer relevant, so why save it? The obvious economic impact of the new technology obscured the need for an appraisal policy to protect the asset value of the content. In effect, the carrier was perceived to be more valuable than the information recorded on it.”

On July 24, 1959 Vice President Richard M. Nixon engaged in a series of exchanges with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park in Moscow. A 16:10 minute recording was made of the exchanges and later broadcast in what would become known as the “Kitchen Debate”.

A black and white photograph taken during the famous “Kitchen Debate” between Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and American Vice President Richard M. Nixon. The original recording of this historical event has disappeared, and has possibly been recorded over.

The color recording of the meeting between the two Cold War leaders was made with RCA cameras and an Ampex VTR, and broadcast the next day on both television and radio. “The video tape, as it appeared on the networks, was clear and certainly preserved the immediacy that is associated w/ live television. On each network telecast, Mr Krushchev’s voice was heard and then lowered in volume as the English translation of each remark was read by announcers in the studio.”

The original recording of this historical event has disappeared, and has possibly been recorded over. The Library of Congress holds a tape of the event that was given by Ampex in order to register its copyright. This tape appears to be the original, however companies usually sent copies, as opposed to originals, to register copyright. The tape held by the Library of Congress begins with a female model in front of the camera, which indicates that these were test images made before the arrival of Nixon and Khrushchev. This recording differs from the original broadcast recording, in that the sound is lower and it is difficult to hear Khrushchev speak.

An unnamed broadcaster holds another recording of the “Kitchen Debate” in a corporate collection. This copy differs from the recording that was broadcast, in that its video quality is poor, indicating that it is a duplication and not the original. Another indication that this is not the master recording is that it is labelled “dub”, which was a slang term for “duplicate”. Unlike the Library of Congress’s copy, this tape has excellent sound and a test pattern bearing the name “RCA”. Another way it varies from the Library’s holding is that it doesn’t feature a female model at the beginning of the footage. Following the “RCA” test patterns are introductions and closings by Frank McGee that are black and white. Although the documentation of this tape says the footage has not been edited, this can not be true due to the appearance of McGee (who was in New York at the time of the event), the footage of Nixon and Khrushchev being in color while McGee’s is in black-and-white, and the absence of footage of the female model.

It must also be noted that when the recording was made, there was anger from the Soviets who wanted to broadcast the Nixon-Khrushchev debate simultaneously with the United States. Philip Gundy, Vice President of the Ampex Corporation, stated at the time that this was an impossibility due to the different broadcast standards (NTSC and SECAM) of the United States and the USSR. The only location that was able to transfer the original recording from NTSC to SECAM was Ampex’s headquarters in Redwood City, California. Completing the transfer would have required the use of the original recording. If this is true, than none of the copies held by anyone accurately represent the footage in the master recording.

In 1995 videotape expert Jim Lindner and the University of California Los Angeles Film and Television archive restored the “Kitchen Debate” using elements from the Library of Congress and a broadcasting company. Unfortunately it is unknown whether or not this restoration accurately represents the original recording, since neither the original documentation nor the original tape is known to exist, and it appears that the only known extant copies are edited versions of the original.

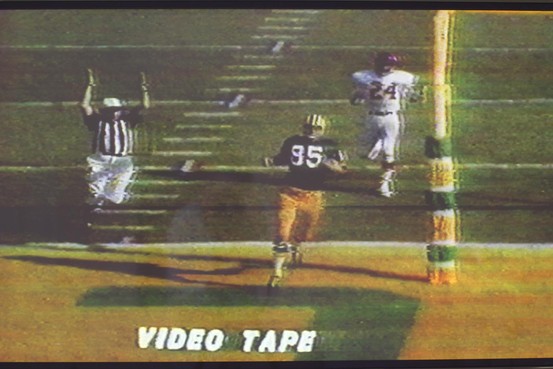

Until recently, any recording of what could be considered the most historically significant sports event to have ever taken place in the United States, was lost. On January 5, 1967 the Green Bay Packers won against the Kansas City Chiefs in the first Super Bowl. Consistent with the lack of preservation strategies by networks at the time of the broadcast, neither NBC nor CBS (the networks that broadcast Super Bowl I) had preserved the original tapes. Since the networks hadn’t preserved the footage, and people did not have video recorders at home, the only known footage that existed of that historical game was sideline footage that was shot by NFL films and about thirty seconds of footage that CBS included in a Pre-Game show for Super Bowl XXV.

A still from one of only two surviving tapes of the 1967 CBS broadcast of Super Bowl I. The two tapes contain almost the entire football game. Prior to their discovery, only thirty seconds of the game was known to exist (The Wall Street Journal).

In the summer of 2005, the Paley Center in New York City was approached by the owner of two 94 minute 2-inch Quad tapes of Super Bowl I. The tapes had been recorded by the owner’s father who worked at WDAU-TV in Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The owner’s father recorded the color footage at his workplace, in the hopes that one day it would be valuable. The owner contacted the Paley Center about restoring the elements after he learned that Sports Illustrated had named the Super Bowl I broadcast one of sports’ “lost treasures” and estimated the broadcast to be worth over $1 million. Doug Warner, the director of engineering at the Paley center, recalled the day when the tapes containing the legendary footage arrived at the center, “This guy showed up with a shopping bag that had Super Bowl I in it.”

The two reels of the 2-inch Quad tape that contained the footage were warped and slightly damaged due to being stored in an attic in Pennsylvania for almost 38 years. After receiving the tapes, the Paley Center had them restored by the Specs Brothers, located in New Jersey. The recording itself isn’t ideal, as it’s missing the half-time show and a large chunk of the 3rd Quarter of the game. In addition, the image quality suffers from occasional eruptions of white static on the side of the screen. Nevertheless, had the one person out of 26.8 million people who saw Super Bowl I not had the vision to recognize the future value of recording the broadcast, this historic footage would have been lost for all time.

Magnetic tape is essentially iron oxide glued onto a mylar base, and tends to be hydroscopic. This can lead to problems of excessive stiction (static friction) and oxide shedding when a tape is viewed during playback, which can cause preservation problems and damage VTRs. In the past, various methods of lubricating a tape were used in an attempt to fix these problems, but it was discovered that “baking” a tape provided the best method for preventing oxide buildup in heads and guides. “Baking” a tape entails placing the tape in an oven or incubator for various periods of time at temperatures of 130º to 140º F. The amount of time needed to bake a tape is dependent upon the width of a tape and the size of the reel.

There are numerous things that make videotape preservation more difficult in contrast to film preservation. One can identify a film’s content, assess the extent of damage and whether it can be viewed via a projector by either holding it over a light source, or measuring its shrinkage using a film shrinkage gauge. The only way to determine what image is on a videotape is to play it back on a VTR, and this is coincidentally the only way to determine how damaged a tape is.

Another way in which videotape contrasts with film is that numerous videotape formats and playback machines have been produced since its introduction, thereby requiring knowledge of the myriad of formats to know which tape can be played on a given machine. Film requires only a cursory glance to know which projector can be used to view it.

The role of standardization was nowhere near as effective with videotape as it was with film. The problems inherent in the lack of standardization began in 1941 when the United States adopted the NTSC (National Television System Committee) broadcast standard which made video produced in the United States incompatible with the United Kingdom’s PAL (Phase Alternating Line) encoding system. As a result, Ampex had to design two separate models of their studio VTRs, one for the NTSC standard and one for PAL. For the next 70 years, nearly every generation of broadcast videotape technology required separate designs in the way signals are encoded on tape, the design of spools, cassettes or VTRs.

It is a general principle that the standard videotape format that is used by broadcasters and producers changes approximately every ten years. When a new format is launched, the format that is displaced becomes obsolete or a “legacy” format. Manufacturers begin to phase out and soon no longer make blank media, equipment or spare parts for the “legacy format”. This creates a serious problem for archivists and collectors who retain collections of tapes on obsolete formats. Prior to digital technology being implemented for storage, archives were engaging in an endless migration from old formats to newer ones. This was both expensive and resulted in generational loss each time the videotape was copied.

In regards to the threat of obsolescence to the preservation of magnetic tape, Ralph Sargent of Film Technology Company in Hollywood, California states, “Speaking in not so technical terms, obviously preserving images captured on magnetic tape presents a two-fold problem. First, the tape has to been in a playable form and second, the reproducing equipment must function properly. This sounds relatively easy but is not always so.”

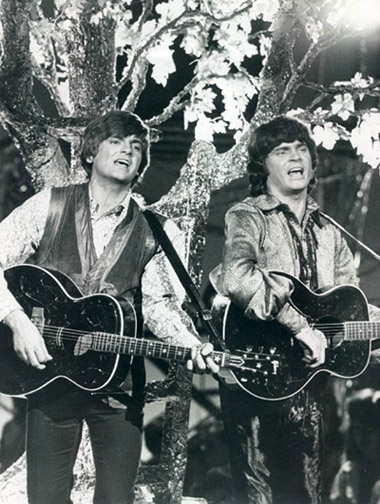

Film Technology encountered this problem in 2001, when they were transferring Episodes 1 and 2 of Johnny Cash Presents The Everly Brothers Show from Type A tape to Digital Betacam for Sony Pictures Entertainment. The Everly Brothers was a 1970 summer show that was broadcast on ABC and had been originally recorded on 2-inch Quad tapes. The 2-inch broadcast master tapes are either lost, or no longer exist and the only copies that are known to have survived are either the off-the-air recordings on Type A or VHS.

Don and Phil Everly perform on Johnny Cash Presents The Everly Brothers Show in 1970. The 2-inch broadcast master tapes of the show are either lost, or no longer exist and the only copies that are known to have survived are either the off-the-air recordings on Type A or VHS.

During the early 1960s Japanese manufacturers were working on ways to reduce the cost of videotape recording equipment which led to the invention of the helical scan method – the most significant improvement made to the quadruplex format. The helical scan method reduced the number of recording heads in a VTR from four to one and resulted in lower costs for the machines.

In 1965 Ampex developed the Type A (the “A” stood for Ampex) videotape, which was similar to the 2-inch Quad in that both were reel to reel and used helical designs. The use of 1-inch tape and the helical scan method made Type A cost significantly less than the 2-inch Quad. The difference in the quality between the two formats is similar to the difference in quality between 16mm and 8mm film.

Ampex developed Type A because it was looking to expand videotape recording into the educational and industrial markets, neither of which could afford the high costs of 2-inch machines or tape. Type A lacked the quality needed for broadcasting, and methods for correcting timing errors. Since the educational and industrial markets didn’t require either of these traits, and Type A was lower in cost, the format was a perfect fit for those markets.

Film Technology had several problems it had to contend with in transferring the recordings of the Everly Brothers Show. Some of these problems were due to the quality of the tape that was used, and others were due to the lack of technical sophistication in the machines that were used to record the show. The tapes which the shows were recorded on were made by Ampex.

In the 1960s Ampex purchased Orr Industries, a tape manufacturing company located in Alabama. At the time Ampex bought Orr, it was notorious for manufacturing shoddy tape under the name of “Irish”. This tape, whether it was 2-inch Quad or 1-inch Type A, caused several problems during recording sessions with its widely varying RF levels and dropouts as well as its tendency to clog heads. It wasn’t until the 1970s that these problems began to subside. In addition the Everly Brothers tapes being poor quality at the time of their manufacture, they also had been used repeatedly prior to the recording of the shows and this contributed to their poor physical condition.

It was uncommon during the 1970s for stand-alone television tuners to be used in non-broadcast facilities. Thus, the recordings that were made of the episodes were not made by a hard-wire feed at ABC, and instead were taped off-the-air somewhere in Los Angeles using either a modified television set or A/V tuner. According to Sargent in his article “Type A and The Everly Brothers Show”, it appeared that the set up for doing these off air recordings was modified on a weekly basis, since the recordings lacked consistency.

The methods that were used in taping the Everly Brothers Show led to uncontrolled video gain which yielded distorted images and over-modulated highlights. It is most likely that the person making the recordings did have the equipment needed to monitor signal levels of either the monitor or picture. Recording off-the-air also led to “ghosting” or “ringing” in the image. “Ghosting” is a series of fainter and fainter repeats of an image from one side or another of the primary image. This is caused by the off-the-air-signal bouncing off of the sides of buildings that were in the line of sight between the transmitter and the receiver of the television signal.

There were additional problems inherent in the preservation and transfer of the Everly Brothers Show tapes, especially since Type A was obsolete by the time Film Technology began working on them. The model of Type A machines used at the time of recording these tapes were not designed to be used as source machines for transfer to a newer format. Transferring material from an older format to a newer one requires solid, time base corrected signals, which these machines were not able to provide. Furthermore, the model of Type A machine that was used by Film Technology for this project was not built to reproduce color using a time base corrector, although it could do so by using a specially modified color monitor. Because of this limitation, Film Technology had to make several modifications to the equipment they were using.

To work around these issues, Film Technology used an Ampex TBC-6 time base corrector, which normally was used with later Type C recorders. The TBC-6 required that the Type A machine be capstan locked to advance sync from the time base corrector and also that a buffered off-tape RF signal be sent to the TBC’s dropout compensation circuitry.

In order to lock the synchronous motor to color sync, parts were used from a Opamp Labs 100 watt audio power amplifier with additional conversion circuitry to feed the motor 90 volts of AC sinewave that was derived from the TBC’s advance sync output. Lastly, the off tape RF was buffered and sent back to the TBC to run the dropout compensator.

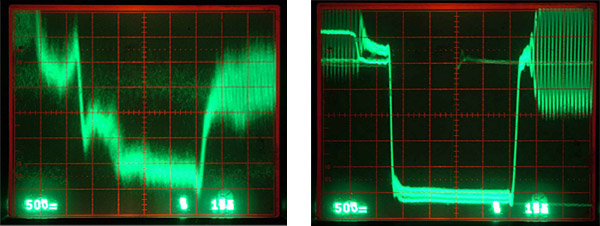

(Left to Right) The uncorrected and corrected signal output from the Type A videotape recordings of Johnny Cash Presents The Everly Brothers Show. Photographs courtesy of Ralph Sargent of Film Technology, Inc.

Yet after all this, the synchronizing signal on the tape was seriously distorted because of the antenna location, the tuner setup and no accurate manual or automatic means of monitoring and adjusting signal levels. The distortion of the synchronizing signal was causing the TBC to look for the start of each line or video field or frame. Thus playback had to be closely monitored and adjusted for level and color saturation or the TBC would shift the horizontal or vertical position of the picture. As Sargent stated, “Manual control of these signals presented the playback operator a “high-wire act” or, seen from another perspective, this was like skating on ice with bum skates or ice made out of Jello. In spite of this the job got done and everyone seemed pretty happy with the results.”

Seven years after the transfer of Episodes 1 and 2 of the Everly Brothers Show, Sony again contacted Film Technology to transfer five additional episodes. This time, Film Technology was able to use two Ampex VR-7800 Type A machines that had been donated to them by an east coast university. Even though these machines were a newer model than the one Film Technology had previously used, they still had to overcome the problem of obsolescence.

An example of one of the Ampex VR-7800 Type A machines used by Film Technology, Inc. to restore two episodes of Johnny Cash Presents The Everly Brothers Show. Photograph courtesy of Ralph Sargent of Film Technology, Inc.

Neither of the machines that were donated were in working order, in fact they were bare-bones products for which locating spare parts is nearly impossible. In working with models of this era, Sargent explains, “On the equipment side, depending on the age of the format, general approaches to the restoration of the equipment must be employed not only for the electronics but also for the mechanical parts of the machine to be employed. If the equipment is very old, this may mean a total refurbishment of the electronics with complete replacement of capacitors and selected resistors as needed. Mechanically, rubber parts, bearings, compressor parts, etc. must be replaced. If the manufacturer no longer supplies new versions of these parts, the duplication facility must be prepared to hire precision fabrication of new parts. The same goes for worn guides and heads.”

The engineering of the VR-7800 machines that were donated to Film Technology was far more advanced than the engineering of their previous incarnations, mainly because they could sync externally without modification. There were also test points on the demodulator cards which could be used to measure off-tape RF and produce initiating pulses for the external TBC’s dropout compensator.

In spite of these features, the non-functioning, donated VR-7800s lacked video processing amplifiers and time base correctors. These amplifiers and correctors were needed to overcome any deficiencies in the tape and to produce a video signal that would be acceptable to transfer the footage to a much newer format.

Given their condition, the VR-7800s would have to be refurbished. This was problematic because not only were the machines obsolete, there were no manufacturer’s manuals or schematics available. In addition, the capstan shaft coverings had completely disintegrated and didn’t leave any indication of what its working diameter was. Almost all of the machines’ operational electronic parts needed to be checked and possibly replaced. Furthermore, since the machines had not been operated in years, there was a significant chance they would not be able to work regardless of the amount of overhauling that was done.

It was decided that it would be best to combine the two non-working machines into one working machine that would serve as the foundation for a serviceable broadcast VTR. The capstan of the VR-7800 was a “split” type that reduced stress to the tape as it passed the rotating video head drum, and this model handled tape much better than the previous model Film Technology used. The restored machine would have a servo-controlled capstan, head drum feed and take-up motors.

Film Technology began the restoration of the machine by recreating the capstan shaft to approximately the correct diameter, and then running a test tape through it to see if it would play. Doing this also allowed them to select which pair of electronic cards were close to working, for which over thirty cards were tested. This successfully produced a recognizable but jumpy picture. It also indicated that if a full refurbishment was done, there was a significant chance of resurrecting the machine to a productive life.

After this stage of the restoration, the outside services of Al Sturm from Wide Band Video Labs were employed. Sturm previously worked on another project for Film Technology and was deemed the correct person to design whatever new or modified equipment would be used to make the Type A machine operate. Sturm would design an interface box to go between the Type A machine and whatever TBC would be used to process its signals. This interface box would either reshape the distorted sync pulses that were coming off of the Everly Brothers tapes, or it would replace them with cleaner ones. Regardless of the condition of the tape sync, a picture that had a minimum of positional shifts was desired.

For general electronic and mechanical restoration of the machine, Ken Zin in Palo Alto, CA was chosen. The machine that had been selected as a foundation for the two-machine combination was driven to Zin’s, along with the selected electronics cards and test tapes. Zin began work by pulling the capstan shaft parts and sending them to George Athon, in San Francisco. Athon owned a company that recoated parts like the capstan shaft with surfaces that matched the characteristics of the original materials on the shaft. He also had done similar work for Ampex when these machines were new, and he had the exact specifications of the shaft diameters.

An example of the Ampex TBC-80 timebase corrector used by Film Technolgy, Inc. in their videotape restoration of Johnny Cash Presents The Everly Brothers Show. The timebase corrector was used to handle unsatisfactory sync pulses coming from the tapes and produce a solid image for the new recordings. Photograph courtesy of Ralph Sargent of Film Technology, Inc.

Once Zin had finished working on the machines, Film Technology began to work on the signal electronics, which were unsatisfactory. They compared three different time base correctors to determine which would be best to handle unsatisfactory sync and produce a solid image, they settled on the Ampex TBC-80. Finally, they implemented Sturm’s hand-built interface unit to couple the VR-7800 with the TBC-80.

Ralph Sargent explains what the interface unit did as:

“1. Take in buffered off-tape RF and playback tachometer pulses and generate the video and dropout pulses which were sent to the TBC causing it to repeat the last line or portion of video where noise pulses (dropouts) occurred in the video. As a result of this processing, the final picture contains but a fraction of the junk that was really coming off tape.

2. Perform sophisticated sync separation from combined video and sync (composite video) in order to generate a window to increase gain during sync time. The off tape sync was then clipped to make a clean sync pulse to be sent to the TBC for accurate timing.

3. Perform low pass filtering to reduce the overall noise in both picture and sync.

4. Provide a cosine equalizer centered at 3.58MHZ. This enabled us to adjust the chroma level since the equalizer on the VR-7800 created more problems than it helped.

5. Pass all new or modified signals on to the Ampex TBC-80.

6) As a final step, a few modifications were made to the Ampex TBC 80 to let it accept the cleaned-up signals from the video processor.”

Though, according to Sargent the results from the VR-7800 and TBC 80 aren’t perfect, he states that most of the recovered video is of greater quality than that which would have been produced from an ordinary 1:1 transfer.

The threat of obsolescence to videotape preservation looms large. When DVDs displaced VHS as the mainstream format for prerecorded media, the writing was on the wall that the videotape era was coming to an end. The last mainstream professional analog format (Betacam SP) faced its demise in 2002 when Sony declared it would cease production of VTRs for the format and it would phase out spare parts availability over seven years.

The rapid pace of technological innovation that existed in the era of videotape has led to the current preservation crisis. Manufactures of videotape often introduced new formats in as little as six months in order to respond to competition and also to champion superior technology. In some cases new formats replaced ones that were commercial failures. This hurried turnover led to formats quickly falling into oblivion, with their parts and machines following suit. As Ralph Sargent stated, “Practically speaking, all analog magnetic video recording media are obsolete these days and probably will never come back to the commercial market again. Therefore, it’s quite reasonable to approach the preservation of these images with the knowledge that the more time that elapses prior to their transfer to more modern recording media will only make that process more and more difficult.”

Videotape was never designed to be a long-term format for storing content and it presents more preservation problems than film. First, a film does not require projection in order to view its content, where as tape requires playback. Furthermore, the machinery that is required to record and playback images on videotape is much more complex than that for film. It would be impossible to construct a 2-inch Quadruplex machine from scratch in order to copy or view tapes that were recorded in the 1950s through the 1970s.

From the beginning of the videotape era in the mid 1950s, numerous historical events that have been recorded on videotape have been in danger of disappearing due to the instability of the format. When the VHS format exploded on the consumer market it became the de-facto populist medium for recording day-to-day life, due to its immediacy, ease of use, cost-effectiveness and ample recording time. Unlike the events that exist on film, those that have been recorded on tape tend to be more candid and serve as a more accurate depiction of the time they document. Since videotape deteriorates at a faster rate than film, it is urgent that we preserve these time capsules so that future generations will be able learn what life was in the last half of the twentieth century.

Bibliography

Books

Enticknap, Leo Douglas Graham. 2005. Moving image technology: from zoetrope to digital. London: Wallflower.

Sargent, Ralph N. 1974. Preserving the moving image. [Washington, D.C.]: Published jointly by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Correspondence

Sargent, Ralph N. <ralph@filmtech.com> “Re:Obsolete Moving Image Technology.” March 11, 2013. Personal e-mail.

Periodicals

By, Richard F.. 1959. Debate goes on TV over soviet protest. New York Times (1923-Current file), Jul 26, 1959. http://search.proquest.com/docview/114737450?accountid=14512 (accessed March 18, 2013).

Roth, David., Diamond, Jared. “Found at Last: A Tape of the First Super Bowl.” The Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2011.

Sargent, Ralph N. , Sturm, Al. “Type A and The Everly Brothers Show” via Personal email. (accessed March 12, 2013)

Websites

Lindner, Jim, “Confessions of a video restorer or how come these tapes all need to be cleaned differently?.”, http://www.media-matters.net/docs/JimLindnerArticles/Confessions%20of%20a%20Video%20Restorer.pdf,(Accessed March 6, 2013).

Lindner, Jim, “Digitization reconsidered.” , http://www.media-matters.net/docs/JimLindnerArticles/Digitization%20Reconsidered.pdf (Accessed March 10, 2013).

Lindner, Jim, “How to care for your originals.” , http://www.media-matters.net/docs/JimLindnerArticles/How%20to%20Care%20for%20Your%20Originals.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2013).

Linder, Jim. “The loss of early video recordings: the nixon-khrushchev \”kitchen debate\.””, http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey/an/an21/an21-7/an21-708.html Abbey newsletter, 21. 7 (1997),(accessed March 9, 2013).

Linder, Jim, “Magnetic tape deterioration: tidal wave at our shores.” , http://cool.conservation-us.org/byauth/lindner/tidal.html (Accessed March 3, 2013)

Lindner, Jim. “Videotape restoration – where do i start?”, Abbey newsletter, 18. 6 (1994), , http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey_new/an/an18/an18-6/an18-612.html (accessed March 9, 2013).