Much has been made about the need to save our priceless cinematic legacy, however preserving this legacy can be tremendously expensive. This expense can often pose a greater threat to the survival of that legacy than physical deterioration itself. I wrote the following paper for Moving Image Archiving: History, Philosophy, Practice course (MIAS 200), taught by Dino Everett, Archivist for the Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive at the University of Southern California.

Over a hundred years after its birth, film has proven to be more than just a popular form of entertainment. It has become a collective visual record of history. It is important to preserve this visual record and to keep it alive for future generations to view. The most important factor in protecting the future of this visual record, more so than the debate over film vs. digital, is funding for film preservation. Simply put, there can be no preservation without funding. In the early 1990‘s, a severe crisis in film preservation was averted with the establishment of the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF). Although the NFPF and donors like David Packard have dramatically changed the landscape of funding for film preservation, there is more to be done.

A brief history of film preservation methods and materials is needed to understand why film needs to be preserved, why preservation costs so much, and why funding for preservation is so important. Film can become fragile and can deteriorate without proper care shortly after its manufacture. Although moving images produced on nitrate-based stock can have a lifespan of over 100 years, nitrate-based stocks are subject to decay and flammability because nitrate’s chemical composition destabilizes over time. As nitrate film deteriorates, it shrinks and as it decays it releases gasses that destroy the emulsion. The processes of shrinkage and outgassing destroy the picture itself, making the film unwatchable.

As nitrate film deteriorates and decays, it releases gasses that destroy the emulsion.

In the early 1950s the problems inherent in nitrate film seemed to be solved with the introduction of acetate base, also known as safety film. Although acetate doesn’t have the flammability characteristic of nitrate, it too is prone to similar methods of decay. Both nitrate and acetate are celluloid plastics that can deteriorate at similar speeds. As acetate deteriorates, like nitrate it can shrink and outgas (also known as ‘vinegar syndrome’). Although acetate’s outgases don’t destroy the emulsion, the shrinkage they cause can render the film unusable. However acetate, if stored properly can survive as long as nitrate.

The basic principle of film preservation is that preservation isn’t viable unless the new medium has a longer life span than the original medium. Until recently, film preservation had been synonymous with film duplication. The primary task to preserve nitrate film was to copy it to acetate stock without excessive loss of quality. Because of the problems listed above for acetate stock, preservation was not just a one-time fix. Equipment and methods have improved over time, along with the stock that film was copied to. Today film is copied to polyester stock, which unlike acetate, is a tough and chemically stable film that is resistant to tearing. Despite its stability, polyester film wasn’t totally embraced by archivists until recently due to early problems with the emulsion separating from the binder. Now, however, duplicating or printing to polyester stock is now seen as the preferred method of preservation. Russ Suniewick of Colorlab Corporation states that in order for a film to be preserved, “It must be put onto another film. The most permanent is polyester film which has a reported life of 1000 years.”

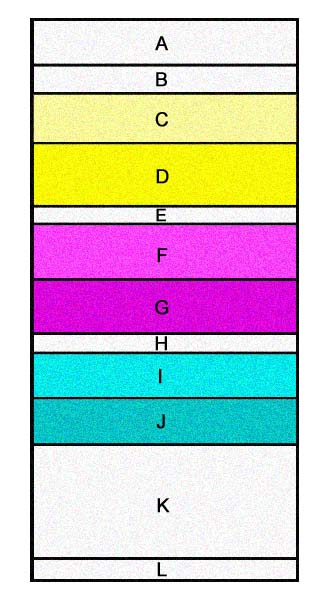

A diagram depicting the many layers of developed color film.

Besides shrinking and outgassing, another issue that leads to film requiring preservation is the color fading that frequently exists in “dye coupler films” such as Eastmancolor. Eastmancolor was a “monopack” stock manufactured by Kodak, that unlike the prior color film of Technicolor, could capture color on a single strand of film. Complex chemistry made the vegetable dyes that were “coupled” in the developing process make certain colors unstable in Eastmancolor prints which over time faded to a dull purple or red. The popularity of Eastmancolor from the early 1950s through the 1970s means that a large portion of movies from this time period suffer from color fading.

35mm Eastmancolor print. The cyan and yellow layers of the emulsion have faded, so that only the red layer is visible.

In duplicating films there has been only one method that has proven to prevent color fading: printing film to black-and-white separations, or YCM masters. In printing black-and-white separations, color film is copied through red, blue and green filters to create three separate black and white records of the film. There is no color fading because there are no dyes being used in the process to create these records. In theory, once these three records are combined, it is easy to reproduce the color that was in the original film the records were struck from. The reality has been that most separations aren’t fully tested at the time they are created to see if they can be recombined due to the prohibitive cost. Separations also are prone to developing preservation problems if they were printed on acetate stock as they can shrink and cause size differences between the three records. These size differences can cause misalignment in the image, and create a fuzzy and unusable image in the new print.

The only method that is proven to prevent or retard color fading, shrinkage, outgassing, vinegar syndrome, flammability and deterioration of film is environmentally-controlled storage. The combined effect on film of lowering both temperature and relative humidity (RH) is remarkable. When storage temperatures are lowered from 80ºF to 60ºF and RH is lowered from 65% to 45% the onset of vinegar syndrome is delayed by approximately 15 years after the film is manufactured. Although the effects of storage conditions aren’t easy to quantify in regards to color fading, its effects on relative rates of color fading are dramatic. By lowering the temperatures from 75ºF to 45ºF, the color fading that would normally occur in 10 years, would instead occur in 100 years.

Unfortunately, climate-controlled storage facilities are very expensive. While major movie studios like Paramount and Warner Brothers can afford such facilities, most public or non-profit archives cannot. The Museum of Modern Art is an exception. Its storage facilities at the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center in Hamlin, Pennsylvania cost $11.2 million dollars when they were completed in 1996. Also, The British Film Institute (BFI), with support from the British government, has spent £12 million (or $19.32 million) to build its storage facility in Gaydon, England. This facility is capable of storing up to 450,000 cans of film in conditions of 23ºF and 35% relative humidity. Though many would scoff at the cost of building such a facility, Robin Baker, head curator of the BFI archive says, “There was years and years of archival practice of endlessly copying to different formats. Just think of the sheer cost. You don’t need to do a massively sophisticated cost analysis to realize just how much cheaper it is to build a vault.”

In 2007 the Library of Congress opened its Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpepper, Virginia. The multi-million dollar facility houses the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of moving images and sound recordings. The 415,000 sq. foot facility contains over 90 miles of shelving for collections storage. It’s climate controlled archives store nitrate film at 39ºF and 30% RH, and safety film at 25ºF and 30% RH. In 1997, David Woodley Packard, of the Packard Humanities Institute (PHI), bought the property the Packard Campus was built on and proceeded to spend millions of dollars to build the state-of-the-art facility. In July of 2007, he donated the campus to the Library of Congress. His gift was tied with Wolf Trap as the second largest private sector gift to the federal government (the Smithsonian Institution being the largest). David Packard and the PFI gifted $155 million dollars in the construction of the campus which was also augmented by Congress’ additional funds of $82 million dollars spent over three years. In 2008, David Packard and PHI donated $39 million to the University of California Los Angeles Film and Television Archive (UCLA) to construct a state-of-the-art storage facility to house the archive’s nitrate collection.The rest of the archive in Santa Clarita is still under construction, and when it is completed in 2013 it will measure between 20,000 to 30,000 sq. feet.

The Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation, located in Culpepper, VA.

Packard has been somewhat of a knight in shining armor when it comes to film preservation as he supplies funds that are desperately needed. An heir to the Hewlett-Packard fortune, he has described himself as a “partially benevolent dictator”. Packard has donated millions to the Library of Congress, UCLA, and to the George Eastman House International Center for Photography and Film. The Packard Humanities Institute, of which he is president, has assets of $2 billion. As Packard described the reasons for choosing such large-scale projects to work on, “”By law, a foundation has to spend 5 percent. We have to spend $100 million a year, so we have a duty to concentrate on big things.”

Prior to the appearance of good samaritans like Packard, and the establishment of the NFPF, film preservation was in a serious crisis. For decades few grasped the importance of what was happening to our nation’s cinematic historical record. In 1960 the filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich wrote an article about the importance of film preservation titled, “Who Cares?” The title of the article reflected the difficulty and lack of interest Bogdanovich was facing in getting the article published.

To give an example of the crisis of film preservation, one only needs to look at the number of films that survive from the early era of motion pictures. The most popular statistic regarding the number of surviving pre-1950 films is approximately 50%, however this number can only be accurate if it applies to feature length films. It must be noted that citing this statistic implies that there are fewer preservation problems with films made after the 1950s, and this is certainly not the case.

Feature films of the 1930’s have been documented to survive at rates of 80-90% while features from the 1920’s have survived at rates of 20%, and features from the 1910’s have survived at rates around 10% (these are copies that tend to have been made from projection prints, as the negatives are almost entirely lost). Survival rates of other types of films, including major studio newsreels and shorts, is even lower. In the past few decades studios have realized the importance of preserving their films for future profit as they are rereleased in new formats, and have taken measures to protect them. Unfortunately, film genres that don’t have the resources of studios, such as documentaries, avant-garde works, anthropological and regional films, advertising shorts and home movies are in danger of being lost to decay. These films remain an priceless visual record of American cultural history.

The crisis in film preservation in the early 1990s stemmed from a decrease in public funding and a growing awareness and rediscovery of films that had fallen into obscurity. These newly-discovered films were deemed worthy of preservation. For independent filmmakers and distributors, along with public and non-profit archives, the primary concern was a lack of funds to adequately preserve their film holdings. Those who worked in the independent film industry often lacked the resources and organizational community to establish expensive asset protection programs for their films.

For archives in the public and non-profit sector, the priority for preservation had been duplicating nitrate film to safety film. As the films decayed, and the demands to access the films increased, there was no method to increase funding so that they could accelerate the pace of preservation and restoration. The smaller and more specialized archives housed inside larger public institutions in this field had to rely on outside grants or gifts to preserve their films on an “as-funds permit” basis because only half received money from their own institutions.

For the decades leading up to the early 1990s preservation crisis, the major channel of federal funding for film preservation had been the American Film Institute (AFI). One of its primary principles when it was established in 1967 was to promote and support the preservation of American films. The AFI is a private, non-profit, non-governmental organization that is supported with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and private donations.

In the late 1960s the NEA established a grant program for film preservation. From 1968 through 1994, the AFI-NEA grant program distributed funds to archives, historical societies, libraries and universities for film preservation. These funds provided a small safety net for genres such as silent films, old independent features, avant-garde works and ethnic features that would normally not receive attention for preservation because they were deemed non-commercial. 50% of the titles copied during this period were made prior to 1929, when silent films were the dominant form of cinema.

The funds distributed by the AFI-NEA were to subsidize laboratory costs of copying decaying films to new film stock. To qualify for an AFI-NEA grant, the applicants were to demonstrate the cultural value and rarity of the films that were in need of copying. Applicants were required to include estimated laboratory costs and to provide matching local funds on a 1 to 1 basis. Grants were awarded by a peer review panel. Approximately 65% of applicants were awarded some amount of funding every year. $5.5 million was awarded from 1979-1992, which stimulated at least twice that amount of money in donations from private donors, and those funds were thus spent on preserving film. During this period, the AFI-NEA program funded the preservation of over 3,300 films and also supported preservation at federal archives such as NARA and the LOC.

Although the impact the AFI-NEA grant program had on the film preservation landscape was initially positive, unfortunately it was subject to declining funding and therefore could not meet the financial demands endangered films presented. Rising laboratory costs, the growing list of preservation problems, and inflation were not taken into account when federal money was channelled by the AFI-NEA to grant recipients. In 1980 the AFI-NEA distributed $541,215 (not counting matching funds from private donors), which was the equivalent of duplicating 159 black-and-white silent feature films. By 1992, the amount of money that was distributed dwindled to $355,600 which could support duplication for fewer than 26 black-and-white silent features. In 1979, the AFI-NEA program funded 82% of preservation projects requested by applicants, while in 1993 only 27% were funded. When adjusted for inflation, by 1992 the AFI-NEA program and the program for the LOC fell to half of its 1980 level. The total federal funding for film preservation through the AFI and LOC (excluding expenditures by NARA) was $796,080.

One of the major issues with the AFI-NEA program was its administrative cost. In 1983 National Center for Film and Video Preservation (NCFVP) was established at the AFI and became the channel for distributing funds for the AFI-NEA program. The NCFVP, was a “pass through” organization that deducted the cost of running the program from the funds the federal government allocated. Beginning in 1985 the annual allowance for the AFI-NEA program was limited to $500,000. $144,000 of that allowance went to the operating costs of the NCFVP’s office in Washington, DC alone.

In October of 1994, Congress announced it was cutting $1.65 million from the budget of the NEA. These cuts included $355,000 from the AFI-NEA preservation program. As a result, the NEA announced it was suspending its AFI-NEA Film Preservation program for copyrighted films. It was determined that copyright holders and organizations like the Film Foundation should share responsibility for preserving copyrighted films. Despite the fact that the films were housed in public archives, the studios still owned the physical elements and copyrights for the films. Eddie Richmond, who was then the president of the Association of Moving Image Archivists protested in a letter sent to NEA Chairman Jane Alexander, saying that the cut in funding made it nearly impossible for public sector archives to support film preservation and seek matching funds from private donors.

In the late 1980s, controversy over the colorization of classic black-and-white films, led a push for legislation to protect these films from alteration. On September 27, 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Interior Appropriations act for the 1989 fiscal year. Included in the funding of this act was the National Film Preservation Act, also known as the “Mrazek Yates amendment”. This amendment contained funding of $250,000 for each year over the next three years to establish the National Film Preservation Board (NFPB) which would be under the control of the Library of Congress. The primary focus of the NFPB was originally to annually select films of cultural and historic importance for inclusion into the National Film Registry. These films would thus be preserved for future generation. In 1992 the legislation was reauthorized and the NFPB focused its energy on a study of the status of film preservation. The study published two separate papers. The first report, entitled “Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current State of American Film Preservation”, focused on the crisis of deteriorating films that were outside the Hollywood studio system, also known as ‘orphan’ films. The second report, “Redefining Film Preservation: A National Plan (1994)” called for a new federally-funded organization that would assist public and nonprofit institutions in preserving orphan films and making them accessible to the public.

On October 11,1996, as a result of the lobbying efforts of the National Film Preservation Board and their studies for Congress, the National Film Preservation Foundation Act of 1996 was signed into law. This law established the National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) and its affiliation with the Library of Congress. The NFPF was created to “promote and ensure the preservation and public accessibility of the nation’s film heritage held at the Library of Congress and other public and nonprofit archives throughout the United States.”

A year later the NFPF began operating as an “independent federally chartered grant-giving public charity…and the nonprofit charitable affiliate of the Library of Congress’s National Film Preservation Board.”

In the first three years of its operation the NFPF had to operate without a budget, as stipulated by Congress, which would in turn force a buy-in. That first year there was barely enough money to hire the executive director, Annette Melville, who had drafted the plan for a national preservation organization. Nor was there enough money for an office, and the NFPF operated out of Melville’s house. At one of the first board meetings, Eric J. Schwartz, a lawyer who helped establish the NFPF, informed Martin Scorcese that there was no money to buy office supplies like pens and paper. Scorcese, and the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), wrote a check on the spot.

In 2000, Congress allocated $250,000 per year to the NFPF, and in the years since has raised the amount three times, this year raising the amount to $1,000,000. Congress set aside this money to be used as matching funds to incentivize donations from the private sector. One million dollars may seem like a significant sum, but it is important to note that in 2011 the NFPF received $1,073,485 in grants and contributions. During that year, the foundation gave $645,092 in preservation grants, while the remaining money went to operational and fund raising expenses. The NFPF actually spent more money than it received: its revenue, less expenses was -$139,110.

Though there are similarities between the AFI-NEA and NFPF programs, the NFPF has proven to be a much more effective model for funding preservation. Funds for the NFPF have increased over its fifteen year existence, while the AFI-NEA program funds decreased in the final decade and a half of its existence. One major difference between the two is the amount of money that is spent operating the organization, and where the funds come from. While the NCFVP took $144,000 out of the $500,000 annual allocation to administer the AFI-NEA program and spent more than 25% of its budget in operational costs, the NFPF raises every penny of its operational costs from outside sources and spends only 5.3% on administrative and development expenses.

The establishment of the NFPF has had a major impact on film preservation, allowing for collections from large non-profit organizations and smaller regional institutions an equal chance at being awarded preservation grants. From 1997-2000, the NFPF distributed awards to only 31 institutions in 16 states and the District of Columbia. The grants saved a total 296 films and collections. In 2011,15 years after its founding, NFPF funds reached 239 archives, libraries and museums in all 50 states including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Funds from the NFPF have helped save a total of 1,870 films since 1997.

In order to receive a grant, applicants must write a short letter describing the cultural significance of the work they are preserving, and an estimate of laboratory cost to preserve the work. A panel of experts reviews the proposals, and awards the funds to applicants. In exchange for the funds, public and nonprofit institutions agree to share viewing copies with the public and store the new masters under conditions that will protect them for decades. Awards from the foundation are modest, as the average grant awarded by the foundation in 2011 was $6,650. These awards are matched by the recipients in staff time and other costs.

One of the great successes of the NFPF has been the repatriation of American films back to the United States. Beginning in the 1910’s, the global popularity of American cinema led Hollywood studios to ship prints of new releases abroad for international audiences to view. Hollywood studios did this expecting that the prints would either be destroyed or shipped back at the end of their theatrical runs. However, many prints were never shipped back mainly due to the cost, and were kept by collectors. Eventually the films became part of New Zealand’s public collections. In 2010 the NFPF and the New Zealand Film Archive (NZFA) announced that a large cache of American silent-era cinema had been discovered in the vaults of the NFZA. Some of the films discovered included John Ford’s Upstream (1927), Maytime with Clara Bow (1923), and Won in a Closet (1914) – the first surviving film directed and starring Mabel Normand. With contributions from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the NFPF was able to examine the rest of the collection in 2011 and made an amazing find: The White Shadow (1924), the first feature that has been linked to Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock served as an assistant director, art director, writer and editor on the film.

The collaboration between the NFPF and the NFZA has repatriated 176 American films from 1898-1929 back to the United States. Approximately 70% of these movies are thought to be the sole surviving copies. The cost of preservation work for these films is supported by private donors and preservation facilities, Turner Classic Movies, and a $203,000 grant from Save America’s Treasures.

Although the grant from Save America’s Treasures can be seen as a success for film preservation funding, it can also demonstrate the instability of funding programs. Save America’s Treasures was a public partnership between the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation that gave hundreds of millions of dollars for the restoration of important historic sites and collections throughout the United States. Unfortunately, like most government funding, Save America’s Treasures was subject to the recent politics of austerity, and in 2011 Congress and President Obama cut its funding entirely. Currently, there are no plans to reestablish funding for Save America’s Treasures and the offices of the program are closed. However, the closing of Save America’s treasures does not affect the current preservation for the repatriated films from the New Zealand Film Archives.

It is important to note that the federal government and its organizations have not been the sole provider of funding for film preservation. Much has been done on a grassroots level. Prior to the NFPF’s existence, when the film preservation crisis was at its peak, creative measures were being taken to raise money for preservation. In 1990 some of Hollywood’s most important filmmakers recognized the plight of deteriorating films and established the Film Foundation. Founded by Martin Scorcese, Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Sydney Pollack, Robert Redford, and Steven Spielberg, the foundation works to increase awareness within the film industry for preservation and increase cooperation between the studios and public archives. The Film Foundation also went directly to the public to convey the urgency of the film preservation crisis, and in March 1993 it collaborated with the cable network, American Movie Classics, to broadcast a three-day festival of preservation. The festival shows features, shorts, films restored by pubic archives, as well as short documentaries, and celebrity interviews on preservation. The festival also solicited donations for preservation via a 1-800 number. After four festivals the Film Foundation and AMC had raised $1.3 million dollars, donating between $25,000 to $50,000 annually to the Library of Congress for film preservation. With the money donated by AMC, the LOC was able to restore All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) at a cost of $80,000.

Telethons raise funds via television, and blogathons raise funds via the internet. So far, three Film Preservation Blogathons have been held, raising money for films and organizations. Authors post essays, articles, commentaries and features regarding classic films on their blogs. Next to the posts, there is a button which readers can click on and donate money to the cause of the blogathon.

Although the federal funding and donations from private foundations have provided the NFPF with a significant amount of money, internet blogathons have provided it with more. The first of the three “For the Love of Film: The Film Preservation Blogathons” raised money for the NFPF and its restoration of two films repatriated from the NZPF – The Sergeant and The Better Man. The second blogathon of the series raised money to help the Film Noir Foundation restore The Sound of Fury (1950) by blacklisted director Cy Endfield. Most recently the NFPF needed $15,000 to stream the restored The White Shadow on its website for four months. From May 13 through May 18, 112 bloggers posted 208 writings and netted $6,490. Although the entire amount needed was not raised, the $6,490 made a significant dent.

Another way to raise money via the internet in a manner similar to a telethon is the Kickstarter.com website. Users post information about the project they are working on and hope to meet their goal through small crowdsourcing donations. Milestone films needed $50,000 to restore the landmark LGBT documentary Portrait of Jason. Unable to provide all of the funding, Milestone turned to Kickstarter.com hoping to raise $25,000. Donors were asked to pledge between $25 to $10,000 (no one donated more than $2,500). From October 11 to December 10, 2012, 310 backers pledged a total of $26,714, exceeding the $25,000 goal.

Although film preservation is more secure than it was twenty years ago, there is much more that needs to be considered regarding its funding. Even though the Congressional allocation for the National Film Preservation Foundation has risen to $1,000,000, that amount is a drop in the bucket in comparison to other programs funded by Congress. Furthermore, the $1,000,000 allocated for film preservation represents the annual salaries of fewer than six rank-and-file members of Congress.

Organizations like the National Film Preservation Foundation and the Packard Institute for the Humanities provide a large portion of the funding, however these funds are finite and are still insufficient to meet the demands of film preservation. Likewise, the addition of grassroots efforts is also not enough to fully fund preservation. Until such time as film preservation of fully funded to meet such demands, we will have to accept the loss of a growing amount of our priceless audiovisual legacy.

Bibliography

Books and Reports

National Film Preservation Board. Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current State of American Film Preservation Volume 1: Report. June 1993. Report of the Librarian of Congress. Washington, D.C.

National Film Preservation Board.

Redefining Film Preservation: A National Plan

Recommendations of the Librarian of Congress in consultation with the National Film Preservation Board. Aug. 1994. Washington, D.C.

National Film Preservation Foundation. Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2000. San Francisco. 30 Mar. 2001

National Film Preservation Foundation. Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2006. San Francisco. 6 Apr.2007

National Film Preservation Foundation. Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2008. San Francisco. 10 Apr. 2009

National Film Preservation Foundation. Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2011. San Francisco. 18 Apr. 2012

Slide, Anthony. Nitrate Won’t Wait: a history of film preservation in the United States. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. 2000

Periodicals

Brown, Mark. “BFI’s new £12m film storage facility to preserve Britain’s reel history”. guardian.co.uk. 29 Aug. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2011/aug/29/bfi-new-film-storage-facility>

Davies, Emma. “Re-record, not fade away”. Chemistry World. Dec. 2011. <http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/Issues/2011/December/RerecordNotFadeAway.asp>

Gaynor, Michael. “Inside the Library of Congress’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation” The Washingtonian. 9 May 2011. <http://www.washingtonian.com/articles/people/inside-the-library-of-congresss-packard-campus-for-audio-visual-conservation/>

Horak, Jan-Christopher. “Surveying AMIA’s First Twenty Years” The Moving Image Vol. 11, No. 1, (Spring 2011): 113-126

King, Susan. “Save That Movie! : After a slow start, AMC’s Film Preservation Festival has raised $1.3 million.” Los Angeles Times. 2 Oct. 1997. <http://articles.latimes.com/1997/oct/02/entertainment/ca-38251>

Lacher, Irene. “NEA Announces New Cuts in Funding : Arts: Agency says $1.65 million reduction in grants is result of congressional budget slashing.” Los Angeles Times. 26 Oct. 1994. <http://articles.latimes.com/1994-10-26/entertainment/ca-54801_1_film-preservation>

La Salle, Mick “A Rich History Worth Saving (With Millions) / Philanthropist David Packard is on a personal crusade to restore film classics” San Francisco Chronicle. 13 Aug. 2000 <http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/A-Rich-History-Worth-Saving-With-Millions-2744249.php#ixzz2F69WgBVA>

Montgomery, David. “Eric J. Schwartz’s love of film fueled his push for preservation of old movies” Washington Post. 12 Aug. 2011 <http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/eric-j-schwartzs-love-of-film-fueled-his-push-for-preservation-of-old-movies/2011/08/11/gIQAa7aoBJ_story.html>

Pierce, David and Schwartz, Eric. “COPYRIGHT, PRESERVATION, AND ARCHIVES: An Interview with Eric Schwartz” The Moving Image. Vol. 9, No. 2, (Fall 2009): 105-148

Schwartz, Eric J. “The National Film Preservation Act of 1988: A Copyright Case Study in the Legislative Process” Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A. Vol. 138 (1988-1989). <http://www.loc.gov/film/pdfs/schwartz%20cop%20society%20journal.pdf>

Websites

About Save America’s Treasures. Accessed 12 Dec. 2012 <http://www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/save-americas-treasures/about.html>

“Best of 2007 Awards: Library of Congress National Audio-Visual Conservation Center Culpeper, Va. Project of the Year – Overall” Online Posting. MidAtlanticConstruction.com <http://midatlantic.construction.com/projects/MA_BestOf2007.pdf>

Doros, Dennis. “Portrait of Jason Restoration”. 11 Oct. 2012. Online Posting. Kickstarter.com. <http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/870959691/portrait-of-jason-film-restoration>

Ferdinand, Marilyn. “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Digital Projection” Online Posting. Ferdy On Films. Accessed 12 Dec. 2012 <http://www.ferdyonfilms.com/2012/dr-strangelove-or-how-i-learned-to-stop-worrying-and-love-digital-projection/15271/>

Ferdinand, Marilyn. “There Is Something I Must Do, There Is Something I Must Do: Hold a Blogathon!” 14 May 2012. Online Posting. Ferdy On Films. <http://www.ferdyonfilms.com/2012/there-is-something-i-must-do-there-is-something-i-must-do-hold-a-blogathon/14255/>

Heath, Roderick. “Coda: For the Love of Film” 21 May 2012. Online Posting. This Island Rod. <http://thisislandrod.blogspot.com/2012_05_01_archive.html>

Heath, Roderick. “For the Love of Film Blogathon” 13 May 2012. Online Posting. This Island Rod. <http://thisislandrod.blogspot.com/2012_05_01_archive.html>

Longley, Robert. “Salaries and Benefits of US Congress Members” 2012. Online Posting. About.com. <http://usgovinfo.about.com/od/uscongress/a/congresspay.htm>

Minderhout, Corey. “A new home for old films”. SignalSCV.Com. 2 Apr. 2012 <http://www.signalscv.com/archives/62793/>

Museum of Modern Art. Film Preservation Center, Buildings. 2 Dec. 2012. <http://www.moma.org/explore/film/bartos/buildings.html>

Pennell, Arden. “Packard makes donation to Library of Congress”. Palo Alto Online News. 6 Aug. 2007. <http://www.paloaltoonline.com/news/show_story.php?id=5590>

Weissman, Ken. “The Library of Congress Unlocks The Ultimate Archive System” 2010. Online Posting. Creative Cow. <http://magazine.creativecow.net/article/the-library-of-congress-unlocks-the-ultimate-archive-system>

Wolfram Alpha. Online Posting. Accessed 11 Dec. 2012 <http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=12%2C000%2C000>

Miscellaneous

H.R. 5893 – Library of Congress Sound Recording and Film Preservation Programs Reauthorization Act of 2008. <http://www.opencongress.org/bill/110-h5893/text>

The National Film Preservation Foundation. Internal Revenue Service Form 990. 2011. <http://www.guidestar.org/FinDocuments/2011/522/055/2011-522055624-0871a960-9.pdf>